US military: robot wars

More money must go to technology to confront China and Russia, say some people in the Pentagon.

When historians come to write about technological innovation in the first half of this century, they are likely to pay special attention to a US Navy drone called the X-47B — otherwise known as the Salty Dog.

When historians come to write about technological innovation in the first half of this century, they are likely to pay special attention to a US Navy drone called the X-47B — otherwise known as the Salty Dog.

Two years ago, the autonomous drone created aviation history when it landed on the deck of an aircraft carrier by itself — that is, without the help of a pilot operating it remotely. Last year the unmanned aircraft marked another first when it refuelled from a tanker while airborne. It went a long way towards demonstrating the potential for semi-autonomous drones to conduct bombing missions over long distances.

For the Pentagon leadership, innovations like the X-47B are centrepieces of a new wave of military technology that officials hope will keep the US ahead of China and Russia, whose heavy investments in recent years has closed the gap.

“We must be prepared for a high-end enemy,” Ashton Carter, the defense secretary, said in a speech last week.

A self-confessed technology geek, Mr Carter is facing his moment of truth. Since he took over as defence secretary a year ago, he has pledged to entrench this technological revolution in the way the Pentagon thinks about its future.

The release this week of the 2017 Pentagon budget will give an indication of whether he is starting to succeed, or if he has been ground down by the department’s vested interests, bureaucratic inertia and daily demands. Over the past two years, the Pentagon has seen many of its proposed cuts to weapons, benefits and bases overruled by Congress, often after lobbying by constituencies within the defence department.

“It is the moment when we see whether or not he has been able to put his rhetoric into reality,” says Shawn Brimley, a former White House and Pentagon official now at the Center for a New American Security. “So far, I have been impressed.”

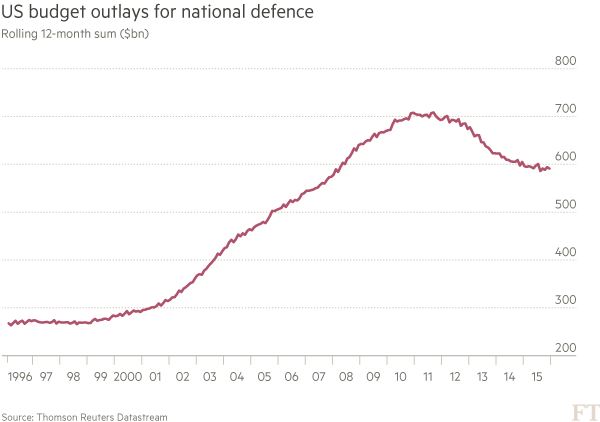

Mr Carter used last week’s speech to try to demonstrate that his plans were gaining momentum, announcing that for the second year in a row, the Pentagon research budget will increase. In 2017 it will be $71.4bn, which will come out of estimated defence expenditure of $582.7bn.

Fewer boots on the ground

American defence leaders have to cope with a split-screen reality. Much of their days are consumed with the fight against Isis, a drawn-out slog that proceeds one bridge, one dusty road and one booby-trapped house at a time.

But after 15 years of grinding conflict in the Middle East, the Pentagon is also gearing up for a new era of what Mr Carter defines as “great power competition”. A graduate in both medieval history and theoretical physics, Mr Carter is trying to galvanise the US defence establishment to think about a future high-tech conflict with China and Russia. Only by reasserting American technological superiority, he argues, can deterrence be maintained.

“The US military will fight very differently in the coming years than we have in Iraq and Afghanistan or in the world’s recent memory,” he said.

The Pentagon calls the new approach its “third offset strategy” after two previous technological surges since the second world war .

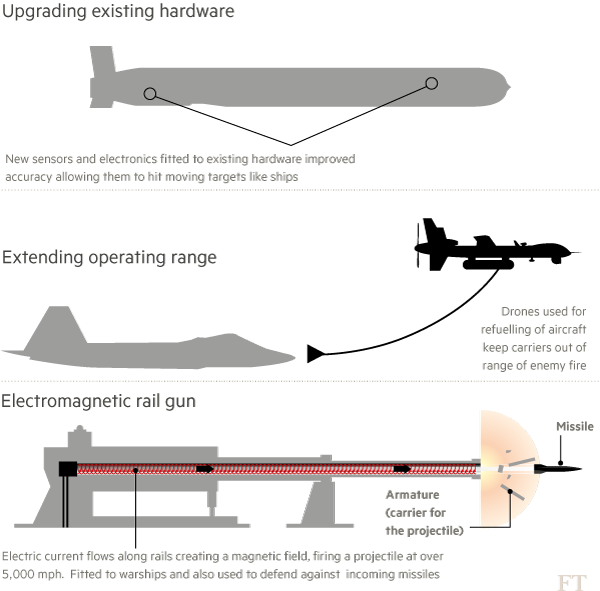

The first was a major investment in nuclear weapons in the 1950s to offset the superiority of Soviet conventional forces. After the Soviets expanded their own nuclear arsenal, the US looked for another edge in the 1970s. The Pentagon invested in technology to reassert US dominance for another generation, including stealth aircraft, precision-guided missiles, reconnaissance satellites and the global positioning system. Spin-offs from this military innovation included the internet.

But over the past decade China and Russia have found ways to blunt those advantages. Beijing’s heavy investment in a wide array of missiles has potentially given it the capacity to overwhelm defences at American bases in Asia and could put at risk aircraft carriers in the region, according to US officials. Russia’s sophisticated air defence systems have allowed it to erect what General Philip Breedlove, the Nato commander, calls “anti-access bubbles” in Syria that would be hard for US forces to penetrate.

“There’s no question that US military technological superiority is beginning to erode,” Robert Work, deputy secretary of defence, said last year.

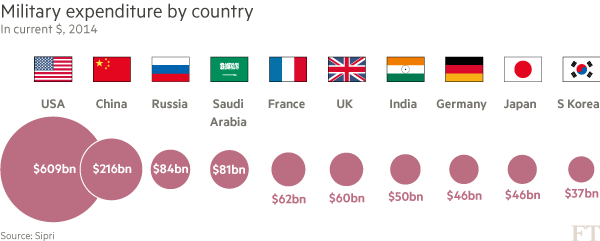

China’s official defence spending of $144.2bn is still only a quarter that of the US, but after double-digit increases for most of the past two decades, experts believe its arsenal of precision and anti-ship missiles as well as anti-satellite weapons represent a genuine challenge to the US in the western Pacific.

The underlying objective of the new strategy is to find weapons and technologies to ensure US forces “can fight their way to the fight” as one official puts it — to evade the layered missile defences both China and Russia can erect, to defend bases against attack from precision-guided missiles and to be able to operate carrier fleets at a much greater distance from an enemy.

For some Pentagon planners, the long-term answers will be found in robotics — be they unmanned, autonomous planes or submarines that can surprise an enemy or robot soldiers that can reduce the risk to humans by launching attacks. Mr Work, who once co-wrote a paper called “Preparing for War in the Robotic Age”, said in December: “Ten years from now, if the first person through a breach isn’t a fricking robot, then shame on us.”

Mass attack

Last week Mr Carter talked about “swarming, autonomous vehicles” — an allusion to another idea that animates current defence thinking in Washington, the use of greater volumes of aircraft or ships in a conflict. The emphasis in American military technology in recent decades has been on developing weapons platforms that are deployed in fewer numbers but boast much greater capabilities, such as the F-35 fighter jet. However, backed by low-cost production techniques such as 3D printing, Pentagon planners are flirting with a different model that seeks to saturate an enemy with swarms of cheaper, more expendable drones.

“It is the reintroduction of the idea of mass,” says Mr Brimley at CNAS. “Not only do we have the better technology but we are going to bring mass and numbers to the fight and overwhelm you.”

Mr Work’s other big theme is the combining of human and machine intelligence, whether it be wearable electronics and exoskeletons for infantry soldiers or fighter jets with suites of sensors and software passing data to the pilot.

He has the bullish belief this will give the US an advantage over its more authoritarian rivals, who are likely to place more emphasis on completely automated solutions because they do not put so much trust in their people. “Tech-savvy people who have grown up in a democracy, in the iWorld, will kick the crap out of people who grow up in the iWorld in an authoritarian regime,” he said.

The vision of a new technological revolution, however, faces a range of obstacles that could undermine the grand plans of Mr Carter. For the Pentagon the process of innovation is the first problem. During previous cycles, a large part of the research was carried out in-house, often promoted by Darpa, the Pentagon agency that seeds long-term projects. But much of this new technology already exists in the private sector — whether it is drones, sensors, cameras or computational power. The challenge for the Pentagon is to devise military applications for commercially available technologies.

Aware of the need for a big cultural shift in the way the Pentagon approaches innovation, Mr Carter has opened an office in Silicon Valley to liaise with the tech sector and is planning another in Boston. There are other new initiatives within the department. Rear Admiral Robert Girrier, who was deputy head of the Pacific Fleet, has been appointed to run a new office called N99 — or the directorate for unmanned systems — to spur new technology applications that can be used in navy drones.

“I saw an advert the other night for a nano-copter that can land in your hand, GPS-enabled, Bluetooth, all of it,” says Admiral Girrier. “This stuff is out there and it is accelerating.”

That leads to a second vulnerability — the pace of technological change. The previous two offset strategies helped give the US an edge that lasted a generation. If, however, the Pentagon can utilise off-the-shelf technologies from the private sector, so can Russia and China. They too are investing heavily in drones and other aspects of robotics.

As a result, any advantages the US manages to establish might be fleeting.

“No one should be under the illusion that a handful of technology breakthroughs, even if they come, are going to guarantee our dominant position for many years ahead,” says Mac Thornberry, the Republican congressman from Texas who chairs the House armed services committee. He believes that only increased spending across the military will sustain the US advantage.

Counting the cost

Some of the hoped-for innovations could also turn out to be prohibitively expensive. Indeed, that is the debate the US Navy is having on drone research. One of the reasons that the X-47B drone attracted so much attention is that it appeared to be the first step towards an unmanned, stealth strike aircraft that could conduct missions over much longer distances than fighter jets — allowing aircraft carriers to operate outside the range of Chinese missiles.

But citing concerns about costs, Navy officials have proposed a much more modest mission for the next stage in its drone development: an aircraft that would refuel existing piloted fighter jets, allowing them to fly longer missions.

Finally, if he wants to spark a wave of innovation, Mr Carter will need to show that he can clear space within a Pentagon budget that is weighed down by the department’s own entitlements crisis — rising salary, healthcare and pensions bills — and by the burden of legacy weapons programmes. At a cost of about $400bn, double the initial estimate, the new F-35 is the most expensive weapons system in history.

As well as increasing the research budget, Mr Carter has already picked one battle with a cherished project. A leaked December memo to Navy secretary Ray Mabus called for a cut in the number of littoral combat ships — a new vessel designed to operate in shallow waters and along coastlines — from 52 to 40 and warned that the navy needed to think “more on new capabilities, not only ship numbers”.

However, defenders of the project hope to restore the spending plans. Rear Admiral Peter Fanta, director of surface warfare, has urged other members of the navy to help him “sell the story” of the ship.

If the “third offset strategy” is to take root, it will need more than just innovation, imagination and collaboration with Silicon Valley — it will also require the Pentagon leadership to have some sharp political elbows.

|

According to Pentagon officials, the 2017 budget will quadruple spending in Europe to challenge what Ashton Carter, defense secretary, calls “Russian aggression”.

To pay for more heavy weapons and exercises in eastern Europe, the Pentagon will ask for $3.4bn in 2017 for its European Reassurance Initiative — a programme it announced in 2014 after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and intervention in Ukraine — up from $789m last year.

“We haven’t had to worry about this for 25 years . . . now we do,” Mr Carter said last week. “Both in Ukraine and in Nato, we are going to have to help countries to harden themselves against Russian influence.” The Pentagon has already announced that it will for the first time place equipment in eastern Europe — tanks, armoured vehicles and missile batteries — for use in Nato exercises aimed at deterring Russia. The new spending request indicates an acceleration in these plans.

Jens Stoltenberg, Nato’s secretary-general, immediately applauded the increased American spending. “This is a clear sign of the enduring commitment by the US to European security,” he said.

The request for a funding increase comes amid an intense debate — both within the Pentagon and Nato — about whether to go a step further and have a permanent troop presence in former Soviet bloc countries.Poland and the Baltic states are eager to secure more long-term US defence commitments: countries such as Germany, however, are less keen to see US bases move farther east.

Nato is also conducting a review of its nuclear policy in response to comments by Russian officials about the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons in the event of a conflict with Nato. For the first time since the end of the cold war, Nato ministers are discussing whether they need to beef up the alliance’s nuclear deterrent.

|

(Source :ft.com)

Post A Comment

No comments :